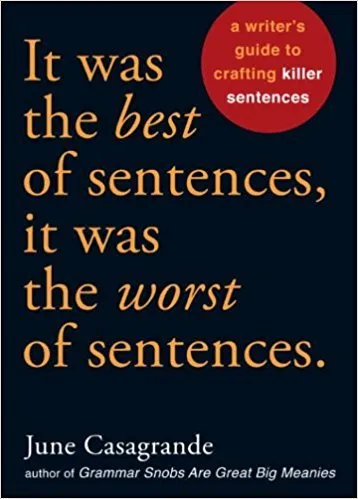

It was the best of Sentences, it was the worst of sentences.

If you want to master the art of the sentence, you must first accept a somewhat unpleasant truth—something a lot of writers would rather deny: The Reader is king. You are his servant. You serve the Reader information.

Page: 8, Location: 114-115

Note: Important

CHAPTER 1 WHO CARES?: Making Sentences Meaningful to Your Reader

Page: 11, Location: 154-155

Note: Chapter

Page: 11, Location: 156

Note: Word

The job of a subordinating conjunction is (drum roll, please) to subordinate. It relegates a clause to a lower grammatical status in the sentence.

Page: 19, Location: 285-286

Note: Important

A lot of experts say that the best way to remember all the coordinating conjunctions is with the acronym FANBOYS, which represents for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so. Others say this is an oversimplification

Page: 22, Location: 325-328

Note: FANBOYS -coordinating conjunction

Subordination means that what was a whole sentence is whole no more. It's a mere subordinate clause. This is why subordinate clauses are often called dependent clauses: they depend on another clause to make the sentence complete.

Page: 24, Location: 363-364

Note: Important

Again, this illustrates that subordination is not a bad thing. It's a tool. It only becomes a bad thing when you subordinate the stuff most interesting to your Reader while elevating less important information.

Page: 25, Location: 376-377

Note: Important

Webster's New World College Dictionary begs to differ. While can indeed be a synonym for although. But it's often a very, very bad one. If the spirit strikes you, vow to use while only by its main definition: "during or throughout the time that."

Page: 29, Location: 433-437

Note: Use of while

As suggests simultaneous action. You brush your teeth as you read the paper. This is one of several definitions of the word.

Page: 28, Location: 424-425

Note: As

It's common to drop a verb after than. We do that because the verb that would come after than is the same as a verb that appeared somewhere before: Joe is taller than Sue is a shortened way of saying Joe is taller than Sue is. Bernice runs faster than Stanley means Bernice runs faster than Stanley runs. But be careful. Your Reader may need a little more help than that.

Page: 32, Location: 478-483

Note: Important

Do you like Coldplay more than Madonna? leaves implied a second occurrence of the verb like, but we don't know who's doing the liking. You could mean Do you like Coldplay more than you like Madonna? or Do you like Coldplay more than Madonna likes Coldplay? There's no rule here other than to remember the pitfalls and be careful.

Page: 32, Location: 484-488

Note: Important

CHAPTER 3 MOVABLE OBJECTS: Understanding Phrases and Clauses

Page: 33, Location: 493-493

Note: Chapter

It's crucial to note that a preposition takes

Page: 35, Location: 529-529

Note: Important

In fact, verbs and prepositions are the only two parts of speech that do this. But not all verbs do. The ones that do are called transitive.

Page: 35, Location: 533-534

Note: Mainly verbs and preposition takes object

However, phrases can be contained within phrases within phrases. So our prepositional phrase with a happily married septuagenarian woman contains other phrases, including the adverb phrase happily, which is modifying the adjective married.

Page: 36, Location: 546-549

Note: Nested Phrases

Also, in a sentence like Joe wanted to cry, the infinitive verb to cry is considered a clause—called a nonfinite clause because it's not conjugated in a way that shows time.

Page: 40, Location: 603-605

Note: Important

In Joe doesn't like crying, the word crying is also considered a nonfinite clause.

Page: 40, Location: 605-607

Note: Nonfinite clause

CHAPTER 4 SIZE MATTERS: Short versus Long Sentences

Page: 41, Location: 615-616

Note: Chapter

Here's how you should look at it: Brevity is a tool. It's a very powerful tool. You don't have to use it. But you have to know how. If you're going to use long sentences, it should be by choice, not due to bumbling ineptitude. Every long sentence can be broken up into shorter ones, and if you don't know how—if you don't see within your long sentences groupings of simple, clear ideas—it will show.

Page: 46, Location: 691-694

Note: Important

If, on the other hand, you're shooting for art, all bets are off. Art and beauty, more so than clarity and expediency, are in the eye of the beholder. If you think you can write an eighty-nine-word sentence that creates for your Reader a better experience than would a ten- or fifteen-word sentence, do. Go nuts. But remember, short sentences can be art, too. Any fan of Hemingway can tell you that.

Page: 57, Location: 862-864

Note: Important

CHAPTER 5 WORDS GONE WILD: Sentences That Say Nothing—or Worse

Page: 57, Location: 873-874

Note: Chapter

A Reader of fiction—be it popular or literary fiction—wants to be told a story. If you can craft metaphors that enhance that story, do. If you can craft metaphors that are so beautiful that they can stand on their own—that they can provide the Reader with as much pleasure as the story—that's an art in itself. But as a rule, if a turn of phrase, a parallel, a comparison, or a metaphor doesn't enhance your Reader's experience, cash it in for straightforward language.

Page: 61, Location: 927-930

Note: Important

The point is: Pay attention to your words. Try not to zone out or become hypnotized by the cliches that live in all our heads and that try to slip into everyone's writing.

Page: 64, Location: 972-974

Note: Important

CHAPTER 6 WORDS GONE MILD: Choosing Specific Words Over Vague Ones

Page: 64, Location: 979-981

Note: Chapter

In fact, choosing generic, overly broad, noncommittal words is a very common mistake of writers at all levels. Writing, as they say, is about making choices. And the sentence is the tool the fiction writer uses to show her Reader that she is fully committed to the choices she has made.

Page: 65, Location: 986-988

Note: Important

Whatever you do, don't let laziness or cowardice dictate your word choices. If you're not sure whether your character likes sardines or sleeps with guys named Ronaldo or wears a brassiere, well, sorry. You must figure that out before you pen your final draft because otherwise you're unfairly burdening your Reader: "Geez, I just couldn't decide what kind of gun she would have, so you figure it out."

Page: 66, Location: 997-1000

Note: Important

Not every sentence needs to be packed with details and descriptors. But learning to pinpoint and root out vague words will give you more choices and therefore more power to construct the best sentence for your piece and for your Reader.

Page: 67, Location: 1020-1021

Note: Important

When people say that adverbs hurt writing, they're talking about a specific kind of adverb, called a manner adverb—even though they may not realize it. Manner adverbs are the ones that describe the manner in which an action occurred: walk quickly, eat slowly, dance enthusiastically.

Page: 68, Location: 1037-1042

Note: Important

But there are also things called adverbials, which may or may not be adverbs: Additionally, there will be cake. In addition, there will be cake. Think of an adverbial as any unit doing an adverb's job: answering when, where, or in what manner, or modifying a whole thought.

Page: 70, Location: 1069-1074

Note: Adverbials

CHAPTER 8 ARE YOUR RELATIVES ESSENTIAL? Relative Clauses

Page: 76, Location: 1161-1162

Note: Chapter

The relative pronouns, according to The Oxford English Grammar, are which, that, and who or whom. Some people include certain uses of where and when, but most authorities don't. Relative pronouns introduce relative clauses:

Page: 78, Location: 1184-1189

Note: Important

George got the job that you wanted. George got the job you wanted. This situation confounds a lot of writers. How do you know when to use that? If you're one of the writers who have puzzled over this, I have good news: it's up to you. Now that you know how to spot a relative clause, you can handle the news that relative pronouns are sometimes optional. When you leave them out, it's called the zero relative.

Page: 83, Location: 1261-1265

Note: Zero relative and that

Remember: relative clauses are modifiers (just like adjectives) but subordinate clauses can be used as subjects and objects (just like nouns). To spot the difference, just determine whether the whole that clause is modifying a noun: The family that stays together. If so, it's a relative pronoun. If that is followed by a whole clause it's a subordinating conjunction: That you love me is all I need to know. Harry learned that life is not fair.

Page: 84, Location: 1274-1279

Note: Two form of that

lady. Prepositional phrases can describe or define nouns—just as adjectives do. Or they can do the work of an adverbial, answering the questions when, where, to what degree, or in what manner or modifying verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, or whole thoughts.

Page: 86, Location: 1314-1317

Note: Important

See, here's the thing about modifiers: people usually expect them to modify the closest possible word, not one that's farther away in the sentence.

Page: 87, Location: 1323-1324

Note: Important

CHAPTER 10 DANGLER DANGER: Participles and Other Danglers

Page: 89, Location: 1361-1362

Note: Chapter

You can also make your participial phrase or clause into a subordinate clause so it's no longer a modifier and therefore no longer has to be right next to whatever it's modifying: While Dan was daydreaming about Nanette, his foot went right into a puddle.

Page: 93, Location: 1413-1415

Note: Important

CHAPTER 11 THE WRITING WAS IGNORED BY THE READER: Passives

Page: 94, Location: 1438-1438

Note: Chapter

It will probably sound familiar: passive voice is a powerful tool in the hands of a skilled writer, but it's brain-numbing poison in the hands of an unskilled writer.

Page: 95, Location: 1455-1456

Note: Important

CHAPTER 12 YOU WILL HAVE BEEN CONJUGATING: Other Matters of Tense

Page: 102, Location: 1555-1556

Note: Chapter

Fiction, too, is often written in the past tense. Novelists and short story writers sometimes choose the present tense, usually for the same reason we saw in the last example: the present tense carries an in-the-moment urgency not found in past tenses, so it's a valid creative device.

Page: 105, Location: 1601-1602

Note: Using present tense to create urgency

Simple past tense is the standard form. It's a safe choice. You can deviate from it, but unless you have a good reason to, maybe you shouldn't.

Page: 106, Location: 1618-1619

Note: Important

These complex verb tenses tell when one action took place relative to when another took place: After having been rejected by NASA and Caltech, Lucky got a job at McDonald's.

Page: 107, Location: 1631-1633

Note: Important

Just remember the when of your story and remember to be consistent and logical.

Page: 109, Location: 1665-1666

Note: Important

CHAPTER 13 THE BEING AND THE DOING ARE THE KILLING OF YOUR WRITING: Nominalizations

Page: 110, Location: 1677-1678

Note: Chapter

These are often called nominalizations. A nominalization is a form of a verb or an adjective that functions as a noun. Some call them buried verbs.

Page: 111, Location: 1688-1689

Note: Important

Phil walks his dog and it's good exercise. You should know the facts. It will help your test score. It's crucial

Page: 113, Location: 1729-1731

Note: Improvements

CHAPTER 14 THE THE: Not-So-Definite Definite Articles

Page: 115, Location: 1749-1750

Note: Chapter

Katie screamed and grabbed the diary. This is rock-solid writing if and only if you've addressed the question what diary? If you've mentioned somewhere earlier in the story that there exists a diary—if you've introduced it—the diary is fine. But if this is the first mention of the diary, that little the sends a bad message to the Reader. It says, "You know. The diary. The one I told you about." Even though you've done no such thing.

Page: 115, Location: 1755-1761

Note: Important

CHAPTER 15 THE WRITER AND HIS FATHER LAMENTED HIS INEPTITUDE: Unclear Antecedents

Page: 119, Location: 1814-1815

Note: Chapter

This problem is called an unclear antecedent. At its worst, this problem can completely ruin a written work: As the sheriff and the bandit fired their guns, a bullet pierced his heart. He fell to the ground. He was dead.

Page: 119, Location: 1820-1822

Note: Hahaha

Whenever you use a pronoun or leave a noun merely implied, just be sure it's clear what you're talking about. If there's any doubt, say outright whatever you had wanted to imply.

Page: 124, Location: 1893-1895

Note: Important

CHAPTER 16 TO KNOW THEM IS TO HATING THEM: Faulty and Funky Parallels

Page: 125, Location: 1904-1905

Note: Chapter

Parallels can be lists of words, phrases, or whole clauses. Each element should be in the same form and should attach in the same way to any shared phrase or clause.

Page: 126, Location: 1920-1921

Note: Important

CHAPTER 17 TAKING THE PUNK OUT OF PUNCTUATION: The Problem with Semicolons and Parentheses

Page: 127, Location: 1942-1943

Note: Important

I suppose this is the very nature of prejudice—isolated bad experiences leading to broad and unfair overgeneralizations.

Page: 128, Location: 1949-1949

Note: Prejudice

Semicolons have two main jobs. First, they help manage unwieldy lists. Second, they separate two closely related clauses that could stand on their own as sentences.

Page: 128, Location: 1955-1956

Note: Important

hermaphrodites,

Page: 130, Location: 1989-1989

Note: Word

"My advice to writers just starting out? Don't use semicolons!" Kurt Vonnegut said in a 2007 speech. "They are transvestite hermaphrodites, representing exactly nothing. All they do is suggest you might have gone to college."

Page: 130, Location: 1988-1990

Note: Hahaha

An article writer's job is to make information easily digestible. But parentheses often amount to force-feeding. They tell the Reader, "I couldn't be bothered weaving all the important facts into a readable

Page: 131, Location: 1994-1996

Note: Important

CHAPTER 18 YOU DON'T SAY: Descriptive Quotation Attributions

Page: 132, Location: 2022-2023

Note: Chapter

In journalism circles, said is a virtue—simple, precise, and unadorned—and alternatives to it are considered frilly and silly.

Page: 133, Location: 2033-2035

Note: Important

An attribution should tell the Reader who was speaking. If possible, it can also convey a bit more information, like emotion. But said shouldn't be thrown out just because the writer is hell-bent on flaunting her uniqueness or creativity.

Page: 134, Location: 2044-2046

Note: Important

CHAPTER 19 TRIMMING THE FAT: Expressions That Weigh Down Your Sentences

Page: 135, Location: 2057-2058

Note: Chapter

this Da Vinci Code sentence contains a classic example of an adjective trying to stand in for real information. Remember, this is the first sentence of the book, and already the author is telling us what to think about one of his characters and shirking his due diligence to show us why this character is renowned.

Page: 137, Location: 2088-2091

Note: Important

If it helps, divide adjectives into two categories: facts and value judgments. Adjectives that express fact can be fine. But adjectives that impose value judgments on your Reader are trouble. Bloodied and limping curator Jacques Sauniere, though awkward, is still better than Awesome and brilliant curator Jacques Sauniere.

Page: 138, Location: 2113-2116

Note: Two sides of adjective

Watch out for manner adverbs that add no solid information: extremely, very, really, incredibly, unbelievably, astonishingly, totally, truly, currently, presently, formerly, previously.

Page: 140, Location: 2133-2134

Note: Important

Also watch out for ones that try too hard to add impact to actions: cruelly, happily, wantonly, angrily, sexily, alluringly, menacingly, blissfully.

Page: 140, Location: 2135-2136

Note: Important

Other flabby figures of speech to watch out for include in terms of for his part, he is a man who, the exact same, taking into account, as if this weren't enough, considering all that—the list goes on.

Page: 142, Location: 2170-2171

Note: Important

Fatty prose can also happen because a writer is reluctant to make a bold statement:

Page: 145, Location: 2220-2221

Note: Important

That's because top publications hate mealy-mouthed allusions and love solid, information-packed statements.

Page: 146, Location: 2226-2226

Note: Important

Just note, for the record, a run-on sentence fails to properly link its clauses: Elephants are large they eat foliage.

Page: 147, Location: 2248-2249

Note: Important

A comma splice, really just a type of run-on sentence, uses commas to link clauses that should stand on their own as sentences or at least be separated with a semicolon or conjunction: Elephants are large, they eat foliage.

Page: 147, Location: 2250-2251

Note: Important

CHAPTER 20 THE MAJOR OVERHAUL: Streamlining Even the Most Problematic Sentences

Page: 148, Location: 2264-2266

Note: Chapter

CHAPTER 21 ON BREAKING THE "RULES": Knowing When to Can the Canons

Page: 164, Location: 2503-2504

Note: Chapter

Every one of the writing "rules" you hear is rooted in a good idea with at least some practical application. Yet none of these rules is worth a damn when stretched into an absolute.

Page: 164, Location: 2513-2515

Note: Important

But remember: These guidelines are always there to fall back on if you get a little lost. Think of them not as rules but as safe havens. If you're getting into trouble with a long sentence, you can chop it into shorter sentences. If your adverb-laden sentence falls flat, you can just ditch the adverbs.

Page: 165, Location: 2519-2521

Note: Important

APPENDIX 1 GRAMMAR FOR WRITERS

Page: 166, Location: 2535-2536

Note: Chapter

To know him is to love him [To know is an infinitive clause functioning as the subject of the verb is; to love is an infinitive clause functioning as a complement of the verb.]

Page: 170, Location: 2597-2599

Note: Note

An adverbial can be an adverb, a prepositional phrase, a clause, or a noun phrase. Though an adverbial may contain crucial information, it is not crucial to the sentence's core structure in the way

Page: 170, Location: 2600-2602

Note: Important

Like adverbs, adverbials can answer the questions when, where, in what manner, and to what degree, or they can modify whole sentences. Or, like adjectives, they can modify nouns. The

Page: 170, Location: 2606-2607

Note: Important

A phrase is a unit of one or more words that function as either a noun, a verb, an adverb, an adjective, or a prepositional phrase.

Page: 174, Location: 2662-2663

Note: Phrase can be even a word

Infinitives and units called participial clauses or participial phrases are also understood as clauses, even though they don't contain an explicit subject: Perry never learned to dance. Ben mastered fencing.

Page: 175, Location: 2671-2674

Note: Important

Clauses are said to be either finite or nonfinite. Finite means they contain a conjugated verb expressing a time element. Nonfinite means that the verb does not convey the time of the action. Infinitive clauses like to dance, in the example, are nonfinite.

Page: 175, Location: 2674-2677

Note: Important

Mood is categorized into three types: indicative, imperative, and subjunctive:

Page: 189, Location: 2887-2887

Note: Important

• The subjunctive mood indicates statements contrary to fact (such as wishes and suppositions), propositions and suggestions, and commands, demands, and statements of necessity. Some uses of the subjunctive are dead or dying. In modern usage, it's most useful to think of the subjunctive as follows: In the past tense, the subjunctive applies only to the verb to be, and it is conjugated as were. The form differs from the indicative only for the first-person singular and the third-person singular.

Page: 189, Location: 2894-2898

Note: Note

Here are some of the most common prepositions: to, with, in, on, from, at, into, after, out, below, until, around, since, beneath, above, before, as, among, against, between, below, and over.

Page: 191, Location: 2920-2922

Note: Important

Some words can function as either prepositions or conjunctions. They include after, as, before, since, and until.

Page: 191, Location: 2922-2924

Note: Important

Adverbs answer the questions • when? I'll be there soon. • where? Bring the laundry inside. • in what manner? Belle and Stan argued bitterly. • how much or how often? Bruno is extremely busy. He is frequently overwhelmed.

Page: 194, Location: 2962-2972

Note: Important

Adverbs can also give commentary on whole sentences. These are called sentence adverbs: Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn

Page: 194, Location: 2972-2974

Note: Important

Adverbs can modify verbs (Mark whistles happily), adjectives (Betty is extremely tall), other adverbs (Mark whistles extremely happily), or whole sentences (Tragically, the crops didn't grow).

Page: 195, Location: 2977-2984

Note: Important

Subordinating conjunctions are a larger group. They include because, if, while, although, though, until, till, as, since, when, than, before, and why and longer expressions such as even though, as soon as, as much as, assuming that, and even if.

Page: 197, Location: 3010-3014

Note: Note

the writer's guiding question: what am I really trying to say?

Page: 6, Location: 90-91

No, it's the act of putting it on paper—forming ideas into sentences—that trips us up.

Page: 7, Location: 105-105

Unlike when we speak, we usually spend time thinking about what we want to say before we write, so we have more time to worry about it and thus overcomplicate

Page: 7, Location: 106-107

Unlike when we speak, we usually spend time thinking about what we want to say before we write, so we have more time to worry about it and thus overcomplicate it.

Page: 7, Location: 106-107

But perhaps the biggest reason that our sentences go bad is that, when we sit down to write, someone is missing. Unlike those bull sessions around the watercooler in which we so adeptly tell stories of concerts and cola consumption, when we write we're all alone

Page: 8, Location: 108-110

Here's another way to think of this: Your writing is not about you. It's about the Reader. Even when it's quite literally about you—in memoirs, personal essays, first-person accounts—it's not really about you.

Page: 8, Location: 118-120

She was focused on the details of her own situation without asking herself which details were relevant to yours.

Page: 9, Location: 125-126

This is the rule: whether you're Christian, Jew, Muslim, or a disciple of the church of Penn Jillette, when you sit down to write, the Reader is thy god.

Page: 9, Location: 133-134

schlepping

Page: 11, Location: 156-156

These are the questions that a skilled newswriter asks: "How will this affect the Reader? Why should he care?"

Page: 12, Location: 176-177

It's deliberate manipulation, and Viewers can smell it a mile away. It works—but the best writing doesn't stoop to this level.

Page: 12, Location: 182-183

To strike a balance between snoozer "the city council voted" sentences and sleazy "there's a killer in your kitchen" sentences, all you have to do is remember the Reader. Ask, "What's important to my Reader?" not just, "What will get his attention?" The answer—be it about the bumpy ride on Main Street or the bottom line on a tax bill—then becomes the main point of your sentence, and your sentence can become a thing of real value.

Page: 12, Location: 183-186

conjunction, which we'll talk about in chapter 2. There's nothing wrong with starting a sentence with a subordinating conjunction in general or with while in particular. But such an opening can, in unskilled hands, pave the way for a problematic sentence. At the very least, it tells the Reader, "Stay put. It could be a while before I get to the point."

Page: 13, Location: 196-199

There's nothing wrong with starting a sentence with a subordinating conjunction in general or with while in particular. But such an opening can, in unskilled hands, pave the way for a problematic sentence. At the very least, it tells the Reader, "Stay put. It could be a while before I get to the point."

Page: 13, Location: 196-199

ameliorates

Page: 16, Location: 236-236

Relative clauses can be great for squeezing in more information— when the information fits.

Page: 17, Location: 252-253

As a writer, it's your job to organize information, to prioritize it with the Reader in mind, to chop and add as you see fit. But only by fully understanding the mechanics of the sentence can you do so in the best possible way.

Page: 18, Location: 271-272

CHAPTER 2 CONJUNCTIONS THAT KILL: Subordination

Page: 18, Location: 273-274

away—one of the least known but perhaps most helpful concepts for writing good sentences: subordinating conjunctions.

Page: 19, Location: 283-284

away—one of

Page: 19, Location: 283-284

right away—one of the least known but perhaps most helpful concepts for writing good sentences: subordinating conjunctions.

Page: 19, Location: 283-284

The problem they can create is sometimes called upside-down subordination. It's a simple concept. It means that a sentence inadvertently takes some less interesting piece of information like John was tired and treats it as though it were more notable than John shot his business partner in the face. Occasionally, that might be exactly what the writer intended. But often it's accidental and undermines the sentence.

Page: 19, Location: 288-292

Conjunctions, as those of you of a certain age will remember from Schoolhouse Rock, are for "hooking up words and phrases and clauses." They're little words like and, if, but, so, and because.

Page: 20, Location: 304-307

Coordinators are a small group that includes and, or, and but. Their job is to link units of equal grammatical status: I eat oranges and I eat apples.

Page: 21, Location: 310-312

Here, the coordinator and is linking clauses that could stand on their own as sentences: I eat oranges. I eat apples. These units are equals. Neither is dependent on the other.

Page: 21, Location: 313-315

A lot of experts say that the best way to remember all the coordinating conjunctions is with the acronym FANBOYS, which represents for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so. Others say this is an oversimplification—that these words don't all work alike.

Page: 22, Location: 325-328

Subordinating conjunctions are a much larger set. They include after, although, as, because, before, if, since, than, though, unless, until, when, and while.

Page: 22, Location: 330-332

A lot of common phrases serve as subordinating conjunctions as well. They include as long as, as though, even if, even though, in order that, and whether or not.

Page: 22, Location: 332-334

These subordinators all have one thing in common: They subordinate. They relegate information to less critical status. They tell the Reader, "This is just minor info we have to get out of the way before we get to the really big news" or "We're tacking this on as an afterthought to really big news."

Page: 22, Location: 335-337

Subordinating conjunctions relegate clauses to lower grammatical status.

Page: 23, Location: 352-352

For example, one subordinating conjunction that seems to sabotage a lot of fiction is as:

Page: 28, Location: 417-418

Some people will tell you this is an out-and-out misuse of while. They say that while can refer only to a time span and can never be used to mean although.

Page: 29, Location: 430-433

Since is a controversial subordinating conjunction. Some people say it can't be used as a synonym for because. They say that since refers to a time span and because refers to cause-and-effect relationships. In fact, dictionaries allow since as a synonym for because. So use it that way if you like, but use it well.

Page: 31, Location: 464-469

A clause is a unit that usually contains a subject and a verb.

Page: 33, Location: 494-495

A phrase is a unit of one or more words that works as either a noun, a verb, an adverb, an adjective, or something called a prepositional phrase.

Page: 33, Location: 495-496

As Stephen King wrote, "Grammar is not just a pain in the ass; it's the pole you grab to get your thoughts up on their feet and walking."

Page: 33, Location: 500-501

A phrase is a single word or a cluster of words that together work in your sentence as a single part of speech.

Page: 33, Location: 505-506

phrases come in five varieties: noun phrases, verb phrases, adverb phrases, adjective phrases, and prepositional phrases

Page: 33, Location: 506-507

Every phrase has a headword—the word on which any other words are hinged. So in Jesse of Sunnybrook Farm, Jesse is the headword, and because it's a noun, this is a noun phrase.

Page: 34, Location: 515-517

It's crucial to note that a preposition takes an object—usually a noun phrase.

Page: 35, Location: 529-529

As we saw earlier, verbs also can take objects. In fact, verbs and prepositions are the only two parts of speech that do this. But not all verbs do.

Page: 35, Location: 533-534

Just remember that phrases can work like nesting dolls

Page: 37, Location: 556-556

The coordinating conjunction and is linking two equally weighted clauses. In fact, these two are so equally weighted that you could swap their

Page: 39, Location: 585-587

The coordinating conjunction and is linking two equally weighted clauses. In fact, these two are so equally weighted that you could swap their order:

Page: 39, Location: 585-587

Not all have two words or even a subject. Most commands, for example, contain only an implied subject. Stop! is a complete clause and even a complete sentence because, in English, commands— called imperatives—drop the subject,

Page: 39, Location: 597-599

clauses are defined as units that usually contain a subject and a verb, but they don't always fit their own definition. Still, if you think of clauses in these simplest terms and just remember that there are exceptions, you'll do fine.

Page: 40, Location: 608-610

gait

Page: 41, Location: 618-618

As a culture, we're becoming ever more inclined to tune out fluff. Stripped-down-bare information is an anomaly that can command our attention and our respect.

Page: 45, Location: 681-682

Another problem with our longer sentence: extra words can have a diluting effect. In I killed him even though I didn't want to because he gave me no choice, the linking terms even though and because seem mealymouthed. It's like the writer is scrambling to explain herself, speaking from a weak, pleading position. It's almost ironic how the facts stand stronger when they stand alone, unmitigated by the writer's urge to overexplain: I killed him. I didn't want to. He gave me no choice.

Page: 45, Location: 683-688

Allow me to end this debate once and for all. Here's how you should look at it: Brevity is a tool. It's a very

Page: 46, Location: 691-692

Here are some other examples of how a clause can work like a noun to serve as a subject: What I want is a soda. How you look is important. Whatever you do is okay with me. That you love me is all I need to know. In all these sentences, the main verb is is, and in all these sentences, the subject—the doer of the action—is a whole clause.

Page: 47, Location: 717-720

By the way, don't feel bad if your sentences come out long and rambling at first. For many people, that's just part of the writing process. I write some major stinkers myself. It doesn't mean you're a bad writer or you lack talent. It just means that your process for writing good sentences involves putting your messy ideas on paper before cleaning them up.

Page: 52, Location: 796-798

So while reworking for clarity, the writer must always keep a tight rein on accuracy and meaning.

Page: 55, Location: 836-837

And it did. Just as he gambled it would. If it helps, divide writing into two categories: craft and art. If you're plying the craft of writing, aim to make many of your sentences short.

Page: 56, Location: 856-857

If it helps, divide writing into two categories: craft and art. If you're plying the craft of writing, aim to make many of your sentences short.

Page: 56, Location: 856-857

Mixing short sentences with long ones can make your writing more rhythmically pleasing and therefore more Reader friendly

Page: 56, Location: 859-860

This problem—the writer paying too little attention to her words—seems most common in news and feature writing. But many novice fiction writers seem to have the opposite problem: They pay too much attention to their words. They try to concoct powerful metaphors.

Page: 60, Location: 913-915

Made-up compound modifiers are always risky. You can say a man is doomed to failure, but are you really nailing it when you call him a failure-doomed man ? Our writer was reaching for a good idea—that Lucy was fated to suffer illnesses.

Page: 63, Location: 953-955

Made-up compound modifiers are always risky. You can say a man is doomed to failure, but are you really nailing it when you call him a failure-doomed man ?

Page: 63, Location: 953-954

Creative writing need not be bound by things like logic or clarity or common sense. But Reader-serving writing requires that we at least consider such alternatives.

Page: 63, Location: 962-963

Writers do this by choosing the most specific words at their disposal.

Page: 65, Location: 989-989

Words like structure and items and person usually have no business in your sentences. They're just wispy shadows of the things they're trying to represent.

Page: 65, Location: 992-995

CHAPTER 7 A FREQUENTLY OVERSTATED CASE: The Truth About Adverbs

Page: 67, Location: 1022-1023

tomorrow. Yep, this tomorrow is an adverb. Don't believe

Page: 68, Location: 1035-1036

Here is the best way to understand what an adverb is. Adverbs answer the questions • when? I'll see you tomorrow. • where? Go play outside. • in what manner? Sue ran quickly. • how much or how often? You're very early. You're rarely late.

Page: 69, Location: 1047-1056

Adverbs also give commentary on whole sentences: Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn. Those are called sentence adverbs.

Page: 69, Location: 1057-1059

And they can create a link to the previous sentence: Consequently, the engine exploded. Those are called conjunctive adverbs.

Page: 70, Location: 1059-1061

Adverbs can modify verbs (Mark whistles happily), adjectives (Betty is extremely tall), other adverbs (Mark whistles extremely happily), or whole sentences (However, I don't care).

Page: 70, Location: 1062-1068

Think of adverb as a word class—a club. Adverbial is a job. And often the dictionary makers get the final say on whether any word does the job enough to earn membership in the club.

Page: 71, Location: 1076-1079

- Adverbs are a very broad group that includes those ~ly words we all learned, but also many other types of words. To identify adverbs, think of them as words that answer the questions when, where, how, to what degree, and in what manner.

Page: 72, Location: 1100-1103

- When someone tells a writer to avoid adverbs, the speaker really means avoid manner adverbs—the ones that answer the questions in what manner and to what degree.

Page: 72, Location: 1104-1106

- Adverbials can be single words or whole phrases that inject when-, where-, or how-type information into your sentence (I'll exercise on Monday) or offer commentary on the whole sentence: Tragically, Jonas was fired. In consequence, he found a new job.

Page: 73, Location: 1107-1112

judgments. You can use an adverb to tell what an action was like: Kevin slammed the door forcefully. But you're better off showing the results of that action: Kevin slammed the door, shattering the wood.

Page: 74, Location: 1133-1136

You can use an adverb to tell what an action was like: Kevin slammed the door forcefully. But you're better off showing the results of that action: Kevin slammed the door, shattering the wood.

Page: 74, Location: 1133-1136

"The loudest person in the room is the weakest person in the room." In our examples, the manner adverbs are supposed to make the action more exciting. But in fact, they weaken the action.

Page: 75, Location: 1142-1144

Like all words, manner adverbs should be carefully chosen. They should carry some benefit that overrides the less-is-more principle. They should not create redundancies, and they should be free of that weak "look at me" quality to which they're so prone. They should not appear to be telling the stuff that your nouns and verbs should be showing.

Page: 76, Location: 1157-1159

track. As such, overuse of relative clauses is disorienting at best and rude at worst.

Page: 77, Location: 1177-1178

A relative clause postmodifies a noun. That's a fancy way of saying that it comes after a noun and describes it. So relative clauses are really modifiers that act like adjectives to describe, qualify, or limit some other word in the sentence.

Page: 78, Location: 1196-1197

And remember, relative clauses are great tools for squeezing extra information into a sentence, but only if that information fits.

Page: 79, Location: 1207-1208

He left early, which was fine by me. Here, the relative clause that begins with which isn't pointing to a noun. It's pointing to a whole idea. These are sometimes called sentential relative clauses.

Page: 80, Location: 1217-1220

First, relative clauses can be either restrictive or nonrestrictive. Second, this distinction is at the center of a controversy over how you can use the word which. Third, there exists something called the zero relative, which refers to the absence of a relative pronoun at the head of a relative clause. Fourth, sometimes it's easy to mistake a subordinating conjunction for a relative pronoun.

Page: 80, Location: 1221-1224

Restrictive and nonrestrictive refer to the job a clause performs in a sentence. A restrictive clause can't be removed from a sentence without harming the point of the main clause: Any house that I buy must be yellow. The relative clause here is that 1 buy. To test whether it's restrictive or nonrestrictive, take it out. You end up with Any house must be yellow.

Page: 80, Location: 1225-1230

They're a big clue. The commas tell you that the information they set off is nonessential, often called parenthetical information. So restrictive relative clauses do not take commas but nonrestrictive relative clauses do.

Page: 81, Location: 1240-1241

Compare these two sentences: The ceremony will honor the athletes, who won. The ceremony will honor the athletes who won. That little comma makes a world of difference. In the first sentence, all the athletes won. In the second sentence, we see that only some athletes won and they're the ones who will be honored. The difference hinges on just one comma because that comma signals whether the clause that follows is restrictive or nonrestrictive.

Page: 81, Location: 1242-1247

Restrictive relative clauses are sometimes called essential relative clauses because they're essential to understanding which thing is being talked about.

Page: 82, Location: 1249-1250

Like that, who can also do different jobs. In the man, who was driving, is tall, the who is a relative pronoun. But in Who was driving? it's not working to modify a noun. It's working as a personal pronoun.

Page: 84, Location: 1279-1283

Relative clauses seem to work best when they cast a little extra light on a thing or an idea. But they can quickly become a problem when they're used to insert history or backstory. They're at their worst when they contain an unstated "Oh, by the way" or "I never took the time to mention this before, so let me squeeze something in now."

Page: 84, Location: 1286-1288

Consider, too, that whenever you have more than one relative clause in a sentence, you might want to break the sentence up. Then again, like Caiman, you might not. Just know that you have the choice.

Page: 85, Location: 1289-1290

CHAPTER 9 ANTIQUE DESK SUITABLE FOR LADY WITH THICK LEGS AND LARGE DRAWERS: Prepositional Phrases

Page: 85, Location: 1290-1292

Prepositional phrases, like relative clauses, are modifiers. But they're more fun because they're so devious.

Page: 85, Location: 1299-1300

Prepositional phrases can describe or define nouns—just as adjectives do. Or they can do the work of an adverbial, answering the questions when, where, to what degree, or in what manner or modifying verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, or whole thoughts.

Page: 86, Location: 1314-1317

Here, the important thing is to remember that prepositional phrases work a lot like adjectives and adverbs and your Reader has some pretty strong ideas about where they should go.

Page: 89, Location: 1359-1360

we'll look at how participial units like walking down the beach and stuffed with chestnuts can also be modifiers. There's just one problem: no one knows whether we should call these units phrases or clauses. And when I say no one, I mean no one.

Page: 90, Location: 1369-1372

participles. Past participles work with forms of have and progressive participles work with forms of be to form different verb conjugations: We have walked, Joe is walking, and so on. But you can

Page: 91, Location: 1386-1390

A participle is a verb form that usually ends in ing, ed, or en. The -ing form is called the progressive participle. The -ed and -en forms are called past participles, though irregular verbs don't follow the pattern: shown, brought, led, dealt, leapt, seen, and so on, are all past participles. Past participles work with forms of have and progressive participles work with forms of be to form different verb conjugations: We have walked, Joe is walking, and so on.

Page: 91, Location: 1381-1389

A participial phrase or clause, then, is simply any participle that serves as a modifier. And it can do so with or without accessories: Exhausted, Harry fell into bed. Exhausted from the long hike, Harry fell into bed. Speeding, Nanette hit a pole. Speeding in her Ferrari, Nanette hit a pole. Eating, Dave almost choked. Eating pastrami, Dave almost choked. Either way, a participial phrase or clause can be seen as a modifier. It modifies a noun or pronoun. So from our examples, who was exhausted? Harry. And who was speeding? Nanette. Harry and Nanette are the nouns being modified by those participial units. Now identify what's wrong with this sentence: Daydreaming about Nanette, Dan's foot went right into a puddle. Either Dan has one smart foot, or we have

Page: 91, Location: 1395-1408

A participial phrase or clause, then, is simply any participle that serves as a modifier. And it can do so with or without accessories: Exhausted, Harry fell into bed. Exhausted from the long hike, Harry fell into bed.

Page: 91, Location: 1395-1398

Either way, a participial phrase or clause can be seen as a modifier. It modifies a noun or pronoun.

Page: 92, Location: 1403-1404

A dangling participle is simply a participle that seems to point to the wrong noun.

Page: 92, Location: 1408-1409

Readers usually expect a modifier to refer to the closest noun.

Page: 92, Location: 1410-1410

You can also make your participial phrase or clause into a subordinate clause so it's no longer a modifier and therefore no longer has to be right next to whatever it's modifying: While Dan was daydreaming about Nanette, his foot went right into a puddle. That's it. That's as hard it gets. Get past the fear of the grammar jargon and you see that dangling participles are very simple. Participles aren't the only things that can dangle: A Kentucky Derby-winning colt, Thunderbolt's jockey was very proud. Did you catch it? We just called the jockey a colt. This is a tricky one because it looks as though the colt, Thunderbolt, comes right after the modifier. But no. We didn't write Thunderbolt. We wrote Thunderbolt's, rendering it a modifier. In the noun phrase

Page: 93, Location: 1413-1422

There's one more danger with participles. Because some are identical to gerunds, they can get confusing: Visiting relatives can be fun. Does this mean that the act of visiting (visiting as a gerund) can be fun, or that relatives who are visiting you (visiting as a modifier) can be fun? We don't know.

Page: 93, Location: 1424-1428

The best way to avoid danglers is to stay vigilant. After a while it becomes a working part of the brain.

Page: 94, Location: 1436-1437

There are two myths about passives that we need to debunk right away: 1. Passive structure is bad. 2. Passive structure is any action-impaired sentence that uses an -ing or -ed verb with a form of to be (like is or was).

Page: 95, Location: 1447-1452

Here's the best way to understand passive voice: it occurs when the object of an action is made the grammatical subject of a sentence. (Technically, it's more precise to say that the passive occurs when the object of a transitive verb is made the subject of a sentence.

Page: 96, Location: 1459-1460

performing the action. But that by phrase is optional. Writers often drop it. And you can't convert the sentence into active form unless you know who or what should be your new sentence's subject.

Page: 97, Location: 1480-1482

But that by phrase is optional. Writers often drop it. And you can't convert the sentence into active form unless you know who or what should be your new sentence's subject.

Page: 97, Location: 1480-1482

If we don't know, we can say someone stole the money or a thief stole the money. But in a situation like this, the best option is often to leave the sentence in the passive. In fact, that's when passives are best: anytime you want to downplay the doer of an action.

Page: 97, Location: 1485-1488

Passive forms dilute that power. In our active form, the action is the verb. In passive form, the verb emphasizes being more than doing. That's what people mean

Page: 101, Location: 1549-1550

Passive forms dilute that power. In our active form, the action is the verb. In passive form, the verb emphasizes being more than doing. That's what people mean when they say that passives are bad.

Page: 101, Location: 1549-1550

The perfect shows that something is fully completed either by the time you're talking about it or by the time indicated.

Page: 103, Location: 1566-1567

But it's obvious that often the simplest verb tense is the best verb tense.

Page: 103, Location: 1578-1578

Most straight news stories are written in the simple past tense. The reason: They tell of things that happened.

Page: 103, Location: 1579-1579

which begins, "Different things move us." But after two paragraphs Updike shifts to the past tense with a simple adverbial device: "Last night." That's where the real story begins.

Page: 105, Location: 1606-1608

the past perfect is used for an "action completed before another."

Page: 107, Location: 1629-1629

The past perfect progressive is used for a "continuing action interrupted by another."

Page: 107, Location: 1629-1630

The future perfect progressive is for a "continuing future action done before another."

Page: 107, Location: 1630-1631

These complex verb tenses tell when one action took

Page: 107, Location: 1631-1632

So verb tenses, like subordination, tell the Reader what information is most important.

Page: 107, Location: 1637-1637

Readers expect the simple-tense stuff to be the main story. The stuff in more complicated tenses is presumed to relate other events to that main story's timeline.

Page: 108, Location: 1642-1643

The Reader had received his time cue. So it was okay to shift into "and from there our story gets under way" mode.

Page: 109, Location: 1660-1661

All the verb tenses and even the passive voice are tools you can use anytime that they work. But simple past tense and active voice are safe choices that can save you anytime you get into trouble.

Page: 110, Location: 1675-1677

Here are some examples of the dreaded beasts called nominalizations: utilization (from the verb utilize) happiness (from the adjective happy) movement (from the verb move) lying (from the verb lie) persecution (from the verb persecute) dismissal (from the verb dismiss) fabrication (from the verb fabricate) atonement (from the verb atone) creation (from the verb create) intensity (from the adjective intense)

Page: 111, Location: 1691-1700

Here are some examples of the dreaded beasts called nominalizations: utilization (from the verb utilize) happiness (from the adjective happy) movement (from the verb move) lying (from the verb lie) persecution (from the verb persecute) dismissal (from the verb dismiss) fabrication (from the verb fabricate) atonement (from the verb atone) creation (from the verb create) intensity (from the adjective intense) cultivation (from the verb cultivate) refusal (from the verb refuse) incarceration (from the verb incarcerate) Obviously, these are all legitimate words. They

Page: 111, Location: 1691-1703

They become a problem only when a writer uses them in place of more interesting actions or descriptions. Nine times out of ten, Barb was happy is better than Barb had happiness or Barb exhibited happiness.

Page: 112, Location: 1703-1706

gerund is the form of a verb that ends in ing and is used as a noun. Outside of a sentence, gerunds are indistinguishable from participles. Singing is hard [singing as a subject = gerund] She was singing [singing as part of verb phrase = participle]

Page: 112, Location: 1708-1713

Combined with a the and of, gerunds can be really bad news: The singing of the song The considering of the job offer

Page: 112, Location: 1713-1716

The walking of the dog is good exercise. = Walking the dog is good exercise. The knowing of the facts will help your test score. = Knowing the facts will help your test score.

Page: 113, Location: 1723-1725

Phil walks his dog and it's good exercise. You should know the facts. It will help your test score. It's crucial that you remember the appointment.

Page: 113, Location: 1729-1731

When you fix a nominalization, you turn the real action into the main verb and you get to bring in the person or thing doing the action. The happiness of the bride was evident. = The bride was happy. That was evident. The refusal of the gift was shocking.

Page: 114, Location: 1736-1739

When you fix a nominalization, you turn the real action into the main verb and you get to bring in the person or thing doing the action. The happiness of the bride was evident. = The bride was happy. That was evident. The refusal of the gift was shocking. = Vanessa refused the gift. I was shocked.

Page: 114, Location: 1736-1740

But don't write off all nominalizations as bad. Without them, this whole chapter couldn't have existed, because nominalization is itself a nominalization.

Page: 114, Location: 1747-1749

imbued

Page: 116, Location: 1768-1768

It's the writer's job to put it in the Reader's hands—to bridge the gap between a state of unknowing and a state of knowing. That's what writing is.

Page: 116, Location: 1770-1771

The best way is to explain immediately after the item. One of the best devices for doing this is a relative clause. Relative clauses, which we know postmodify nouns, can come soon after a word to add description or clarity to it: Katie screamed and grabbed the diary that her mother had given her.

Page: 116, Location: 1779-1781

rumination

Page: 117, Location: 1786-1786

And if you doubt that the has unique importance, consider this: It's the only word in the English language that is its own part of speech. It's in a category all its own. The is called the definite article. It's distinct from a and an, which are called indefinite articles, and it's distinct from this and these, which are called demonstratives. The stands alone. So, now that I've thoroughly slammed using the to refer to stuff heretofore unknown to the Reader, how can we explain an all-too-common use of the like the one found in the very first sentence of the novel Travels in the Scriptorium, by Paul Auster? The old man sits on the edge of the narrow bed, palms spread out on his knees, head down, staring at the floor. Auster has not yet introduced the old man. He didn't say an old man. He didn't say there is an old man. He hasn't told us there exists an old man, or a bed or a floor either, for that

Page: 117, Location: 1790-1805

And if you doubt that the has unique importance, consider this: It's the only word in the English language that is its own part of speech. It's in a category all its own. The is called the definite article. It's distinct from a and an, which are called indefinite articles, and it's distinct from this and these, which are called demonstratives. The stands alone.

Page: 117, Location: 1790-1797

If the suggests familiarity, then putting the in front of something so surely unfamiliar suggests that familiarity will come. It foreshadows. It teases. The Reader knows that the writer is going to explain who the old man is. The writer is asking for the Reader's trust and promising something in return. It's a great device that skillful writers use all the time. It demonstrates the power of the.

Page: 118, Location: 1808-1813

possessive determiners (think of these as adjective forms of possessive pronouns): my, your, his, her, its, our, their

Page: 120, Location: 1832-1833

relative pronouns: that, which, who, whom

Page: 120, Location: 1834-1834

Don't let the term unclear antecedent intimidate you. It means exactly what it sounds like: that it's unclear which prior thing is being referred to.

Page: 120, Location: 1839-1841

Make it a habit to scrutinize every him, her, and so on, to be sure they're clear.

Page: 121, Location: 1847-1848

There's nothing wrong with leaving things implied as long as the implication is clear and doesn't make your Reader stumble: Kelly is crazy. Ryan is, too. Implications only work if the Reader gets them. We don't say what Ryan is. We leave it implied. Yet it's perfectly clear. He's crazy.

Page: 123, Location: 1886-1889

But when you can find no synonyms or other embellishments to point squarely at your antecedent, repetitiveness is better than chaos. It's better to repeat the word bandit than to refuse to tell your Reader which one of your pivotal characters met his demise.

Page: 124, Location: 1902-1904

Parallel form relies on Reader expectations. When Readers see something in list form, they expect it to be a list:

Page: 125, Location: 1916-1917

Parallel form relies on Reader expectations. When Readers see something in list form, they expect it to be a list: Pablo has visited Maine, Idaho, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and New Jersey.

Page: 125, Location: 1916-1917

When you include an element that doesn't work like the others, you betray those expectations: Pablo has visited Maine, Idaho, Pennsylvania, loves Georgia, and New Jersey.

Page: 126, Location: 1918-1919

If the writer believes that these independent clauses are so closely-linked that they belong in the same sentence, it's not my place as a copy editor to disagree.

Page: 130, Location: 1982-1983

I try to keep my prejudice in check. If I come across something like this, I leave it: Holly hadn't had a drink for weeks; she wanted one badly. If the writer believes that these independent clauses are so closely-linked that they belong in the same sentence, it's not my place as a copy editor to disagree. But when I'm the writer, I just separate the sentences.

Page: 130, Location: 1979-1984

transvestite

Page: 130, Location: 1989-1989

An article writer's job is to make information easily digestible. But parentheses often amount to force-feeding. They tell the Reader, "I couldn't be bothered weaving all the important facts into a readable narrative, so I just crammed them in here."

Page: 131, Location: 1994-1996

Sometimes, parentheses really are the best way to serve the information to the Reader. Usually, the smaller the parenthetical insertion, the better it works. The more stuff crammed between the parentheses and the more parentheses crammed into the sentence, the bigger the clue that the sentence needs an overhaul.

Page: 131, Location: 2000-2002

vertiginous

Page: 131, Location: 2005-2005

Parentheses can also be used as a sort of voice device—slipping in wry observations, ironies, exclamations, and other little bits of commentary: George told me he was going out for a pack of cigarettes (yeah, right) and that I shouldn't wait up.

Page: 132, Location: 2016-2018

I edit a writer who does this a lot: "The menu is all new," Jones enthused.

Page: 132, Location: 2024-2025

A quotation attribution is not an ideal place to squeeze in tons of extra information. When the result feels artificial, just make a new sentence or two.

Page: 134, Location: 2052-2053

If you like to get creative with quotation attributions, do. But do so because it works, not because you want to show off or be different. When in doubt, remember that said is an old friend you can always fall back on.

Page: 134, Location: 2055-2057

Because of the Reader. His time is valuable, his attention span may be short, his opportunities for diversions are infinite, and his willingness to read your writing is a blessing for which you should be grateful. Don't waste his time. Learn to root out flabby writing and to streamline sentences to make every word count.

Page: 135, Location: 2066-2069

There's a difference between fatty sentences and long sentences. Yes, they're often one and the same. But not always. A 134-word sentence can be tight and economical, while an 8-word sentence can contain 7 words of lard—or even 8.

Page: 135, Location: 2069-2071

It can take the form of an unnecessary adverb, a ridiculous redundancy, a self-conscious over-explaining, a cliche, or jargon.

Page: 136, Location: 2072-2073

hypochondriac

Page: 137, Location: 2096-2096

No doubt, that's what some more critically acclaimed writers would have done: Jacques Sauniere staggered through the archway of the museum's Grand Gallery. Adjectives

Page: 138, Location: 2107-2108

Adjectives aren't bad. They can be wonderful, and as predicates they can work perfectly: Frau Helga was tall. But adjectives are no substitute for solid information. Often they have that less-is-more thing working against them: The big, terrifying, homicidal, totally out-of-control escaped convict ran toward me does not achieve its desired effect. Better to just say, The escaped convict ran toward me and leave it at that.

Page: 138, Location: 2108-2113

But adverbs can also create redundancies: already existing, previously done, first begin, currently working.

Page: 139, Location: 2127-2128

All these words have their place. They appear in the best writing, but more often they're found in the worst writing. So consider them red flags and weigh their use carefully.

Page: 140, Location: 2136-2137

Not every in addition to is bad. Sometimes it's a valid choice. But usually, in addition to refers to something that's already been discussed at length.

Page: 140, Location: 2143-2145

In other words, she was saying, "In addition to the stuff I just told you about, here's another thing."

Page: 140, Location: 2147-2147

This brings us to another problem with our original sentence: The in addition to phrase introduces a clause that contains the word also. This is a redundancy. It renders the entire in addition to phrase a complete waste.

Page: 141, Location: 2149-2151

"The expression the fact thatshould be revised out of every sen-tence in which it occurs."

Page: 141, Location: 2159-2160

I'm more liberal on the fact that. Sometimes it's the best way to show that an abstract concept is functioning as a noun: That Robbie steals means he's a thief. The fact that Robbie steals means he's a thief.

Page: 141, Location: 2162-2165

I'm more conservative on due to the fact that. That's just a tedious way of saying because.

Page: 142, Location: 2168-2170

He is a man who and other terms with this structure are especially troubling: It is a place that, dancing is an activity that, John's is a house that, cooking is a thing that. They

Page: 142, Location: 2172-2173

He is a man who and other terms with this structure are especially troubling: It is a place that, dancing is an activity that, John's is a house that, cooking is a thing that.

Page: 142, Location: 2172-2173

They all follow the form noun/pronoun + to be + noun/pronoun that refers to the same thing as first + relative pronoun This structure shifts the focus away from the important stuff by dedicating the main clause to ridiculously obvious information: He is a man who works very hard. Paris is a place that gets snow.

Page: 142, Location: 2173-2178

In all these sentences, the new information is trapped in the relative clause—those clauses that begin with that, which, who, or whom and that

Page: 143, Location: 2180-2181

In all these sentences, the new information is trapped in the relative clause—those clauses that begin with that, which, who, or whom

Page: 143, Location: 2180-2181

The main clause is devoid of new information. It has the same problem as the upside-down subordination we covered in chapter 2 because the most interesting information isn't getting top billing in the sentence.

Page: 143, Location: 2181-2183

To fix a sentence with this structure, just make the new information your main clause:

Page: 143, Location: 2183-2184

In fact, I can't think of a situation in which for so-and-so's part is better than just for so-and-so.

Page: 143, Location: 2191-2192

A from ... to construction can set up a very long introductory phrase. The main clause has to wait until the from . . . to observation is complete, which can take a while.

Page: 144, Location: 2204-2206

No matter how long, a from blank to bank construction usually works as a modifier. It's not hard to understand why an eight-, ten-, or twenty-word modifier can be cumbersome.

Page: 144, Location: 2206-2208

My best advice here is don't rely on this construction too much and be prepared to abandon it if it starts to get unwieldy. If your from or your to contains its own from or to, you're probably making a mess,

Page: 144, Location: 2208-2210

Remember: from blank to blank to blank is comma free even when your blanks are so long that they make you forget you were using this construction in the first place. Of course, that's probably a sign that your from ... to setup isn't cutting it.

Page: 145, Location: 2218-2220

In other words, fatty insertions that can seem so meaningful when we're writing are often unnecessary at best and insufferable at worst. When in doubt, take them out.

Page: 146, Location: 2236-2237

Elephants are large. They eat foliage. Elephants are large; they eat foliage. Elephants are large, and they eat foliage. Elephants are large because they eat foliage.

Page: 147, Location: 2253-2255

Remember that your goal is not fewer words, but economy of words.

Page: 148, Location: 2261-2261

Whenever you're faced with a problem sentence, start by looking for its main clause—that is, its main subject and verb:

Page: 148, Location: 2269-2270

Any sentence built on a foundation of has + noun or pronoun + present participle stuffs the action into a participial phrase or clause: The plan has them speculating. To make speculating a real action, you'd have to rejigger the whole sentence: Since the government announced plans to rid banks of lethal assets, precious metals investors are speculating that the economy and lending groups may be reviving.

Page: 156, Location: 2388-2393

Another activity at the Family Fun Center is the opportunity for kids to create a journal. This has that a blank is a blank structure as its main clause, stating little more than an activity is an opportunity. You'd do better to make the main verb a real action: Kids at the Family Fun Center can also create a journal.

Page: 159, Location: 2424-2428

When you lay out two options, there's no need to first insert a sentence saying that you're about to lay out two options. Also, after the writer said she was about to lay out two options, she dedicated a whole sentence to evaluating one of the options she had yet to lay out. Whenever you find yourself buried under so many words, start by asking: can't I just chop all this out? The answer is usually yes.

Page: 161, Location: 2456-2460

The point is, either explain or don't. But don't half-ass

Page: 163, Location: 2486-2487

The point is, either explain or don't. But don't half-ass it.

Page: 163, Location: 2486-2487

All the so-called rules are really just guidelines that can help you serve your Reader—or not. If they help you, use them. If not, disregard them entirely. You'll be in good company.

Page: 165, Location: 2517-2518

All the so-called rules are really just guidelines that can help you serve your Reader—or not. If they help you, use them. If not, disregard them entirely. You'll be in good company. But

Page: 165, Location: 2517-2519

name Philip Roth on the cover. Perhaps

Page: 165, Location: 2526-2526

Perhaps that's unfair. Perhaps not. Maybe it means that Readers expect us to earn their respect before they'll give us the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps abstract painters have to deal with the same thing—they must prove they can draw a bowl of grapes before people will admire their abstract shapes or spatters

Page: 165, Location: 2526-2528

An indirect object is in essence a prepositional phrase that comes before the direct object and that, in its new position, no longer requires the preposition: Robbie made spaghetti for his mother. [His mother is the object of the preposition for.]

Page: 168, Location: 2564-2568

A complement of a copular verb is not the same as an object of a transitive verb. An object receives the action of the verb, but the complement of a copular verb refers back to the subject: Anna seems nice.

Page: 168, Location: 2575-2578

An object of a transitive verb can have its own modifying complement. This is called an object complement (or an object predicative). The object complement can be an adjective phrase or a noun phrase. It describes the object or tells what the object has become: Spinach makes Pete strong. [The adjective strong is a complement of the object Pete.]

Page: 169, Location: 2580-2584

Birds make nests and they sing, [compound sentence containing two coordinated clauses of equal grammatical weight]

Page: 169, Location: 2590-2591

A sentence with more than one independent clause is a compound sentence. In a compound sentence, the clauses can be coordinated with a coordinating conjunction. Coordinate clauses have equal grammatical status. A

Page: 169, Location: 2587-2589

A sentence with more than one independent clause is a compound sentence. In a compound sentence, the clauses can be coordinated with a coordinating conjunction. Coordinate clauses have equal grammatical status.

Page: 169, Location: 2587-2589

Birds make nests and they sing, [compound sentence containing two coordinated clauses of equal grammatical weight] Because Andy is hungry, he eats, [complex sentence containing a subordinate clause and a main clause]

Page: 169, Location: 2590-2592

An adverbial can be an adverb, a prepositional phrase, a clause, or a noun phrase. Though an adverbial may contain crucial information, it is not crucial to the sentence's core structure in the way that subjects, verbs, objects, and complements are.

Page: 170, Location: 2600-2602

Like adverbs, adverbials can answer the questions when, where, in what manner, and to what degree, or they can modify whole sentences. Or, like adjectives, they can modify nouns.

Page: 170, Location: 2606-2607

The van followed Harry to the park, [prepositional phrase answering the question where]

Page: 171, Location: 2607-2609

The van followed Harry this afternoon, [noun phrase answering the question when]

Page: 171, Location: 2610-2611

In addition, the van followed Harry, [prepositional phrase connecting the sentence to a prior thought]

Page: 171, Location: 2612-2613

The van followed Harry where he walked, [whole clause answering the question where]

Page: 171, Location: 2615-2616

Declarative sentences (statements) can be made into interrogatives (questions) by switching the positions of the subject and the operator, which is the first word in the verb phrase or the dummy operator do:

Page: 172, Location: 2629-2631

Dolphins are clever, [declarative] Are dolphins clever? [interrogative formed through inversion]

Page: 172, Location: 2631-2632

Storytelling has been part of our culture for centuries, [declarative] Has storytelling been part of our culture for centuries?

Page: 172, Location: 2633-2634

You like cake, [declarative; could also be expressed with a dummy operator as You do like cake] Do you like cake? [interrogative formed with dummy operator do]

Page: 172, Location: 2635-2637

In writing, this can be represented as a positive statement followed by a question mark: That's what you're wearing? You'll he there on time?

Page: 172, Location: 2638-2639

A sentence fragment is an incomplete sentence: That's what he wanted. Money.

Page: 173, Location: 2642-2643

Cleft sentences use it + is or was and a relative pronoun like that or who to add emphasis. So, Leo saved the day. made into a cleft sentence becomes It was Leo who saved the day.

Page: 173, Location: 2645-2650

Existential sentences put there is or there are at the head of a sentence for emphasis: Aliens are in the building. becomes There are aliens in the building.

Page: 173, Location: 2650-2654

• Left dislocation, in which the subject gets bumped to the left and a repetitive pronoun takes its place: Cars, they're not what they used to he.

Page: 174, Location: 2655-2656

• Right dislocation, in which the pronoun duplicates the work of a subject and the subject is bumped to the right: They have a lot of money, Carol and Bill.

Page: 174, Location: 2657-2658

• Other rearrangements, such as a prepositional phrase moved to the front of a sentence: To the mall we will go.

Page: 174, Location: 2659-2660

They come in different types: • personal pronouns, subject form: I, you, he, she, it, we, they • personal pronouns, object form: me,you, him, her, it, us, them • indefinite pronouns: anybody, somebody, anything, everything, none, neither, anyone, someone, each, nothing, both, few, and others • possessive pronouns: mine, yours, his, hers, its, ours, theirs • relative pronouns: that, which, who, whom • interrogative pronouns: what, which, who, whom, whose, whatever, whichever, whoever, whomever, whosever • demonstrative pronouns: this, that, these, those • reflexive pronouns: myself, yourself, yourselves, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, themselves (These words refer back to a subject—He saw himself in the mirror, or they are used for emphasis—I, myself, don't like the tropics.) • other pronouns: the existential there, several uses of it, the substitute one

Page: 178, Location: 2720-2736

Determiners introduce noun phrases and can provide information about possession, definiteness, specificity, or quantity: • possessive determiners: my, your, his, her, its, our, their • articles: a, an (indefinite articles); the (definite article) • demonstratives: this, that, these, those • wh- determiners: which, what, whose, whatever, whichever, and so on • quantifiers and numbers: all, both, few, many, several, some, every, each, any, no, one, five, seventy-two, and so on

Page: 180, Location: 2759-2768

Unlike a transitive verb, which takes an object (Dan eats cheese), a copular verb takes something called a complement (Dan seems dishonest). Where a transitive or intransitive verb would take an adverb (Nancy works happily), a copular verb takes an adjective (Nancy is happy).

Page: 184, Location: 2807-2814

Some verbs can have both copular and noncopular forms, depending on meaning: Neil acts badly (not copular) means Neil is an unskilled thespian. Neil acts bad (copular) means he acts as though he is bad.

Page: 184, Location: 2814-2820

Verbals are verb forms that work as other parts of speech. They are • gerunds—the -ing form of a verb working as a noun: Dancing is good exercise. • participles—usually an -ing, -ed, or -en form. When a participle works as a modifier instead of as part of a verb, it qualifies as a verbal: A man covered with bee stings came into the hospital. A child skipping to school is probably happy. • infinitives—a verb form introduced by the infinitival to: to run, to know, to become. Infinitives can act as subjects: To know him is to love him. But infinitives are also said to act as adjectives by modifying nouns (There are many ways to travel) and as adverbs by modifying adjectives (I am happy to help).

Page: 185, Location: 2828-2846

• Indicative is the most common mood. Sentences in the indicative are usually statements, also called declaratives: Sal washes the dishes. Interrogatives (questions) and exclamatives

Page: 189, Location: 2888-2890

(exclamations) are also categorized as indicatives, with their verbs behaving similarly to the verbs in statements.

Page: 189, Location: 2890-2891

• The imperative mood is used for commands: Wash the dishes. Imperatives are considered complete sentences. The subject is implied. It is you: [You] Wash the dishes.

Page: 189, Location: 2891-2893

Modality is most helpful for understanding modal auxiliary verbs. Modal auxiliaries such as can, may, might, could, must, should, will, shall, ought to, and would deal with factuality or human control: William can help uses the modal auxiliary can to address human control. That coffee might be decaf uses the modal auxiliary might to address factuality.

Page: 190, Location: 2904-2910

The best way to understand prepositions is to look at how they form prepositional phrases. A prepositional phrase is a preposition and its object.

Page: 191, Location: 2918-2919

The object of a preposition is a noun phrase, which can be a noun or a pronoun with or without determiners and modifiers: Megan studied with Joe. The dogs are at the grassiest park in town.

Page: 192, Location: 2930-2933

Prepositional phrases can be understood as modifiers or adverbials.

Page: 193, Location: 2952-2952

Prepositional phrases can modify nouns: the man with the red hat.

Page: 193, Location: 2952-2954

They can modify actions: She sings with enthusiasm.

Page: 193, Location: 2954-2955

Prepositional phrases can also function at the sentence level, answering questions like when and where. He will meet you at the corner. In the morning,

Page: 193, Location: 2956-2958

they can modify whole sentences: In Addition, note the location of the exit.

Page: 193, Location: 2959-2961

Adverbs can also create a link to a previous sentence. These are called conjunctive adverbs: However, the parade was a success.

Page: 194, Location: 2974-2976

Certain subordinating conjunctions that convey time, including before, since, and until, are also used as prepositions.

Page: 197, Location: 3014-3016

PUNCTUATION BASICS FOR WRITERS

Page: 198, Location: 3022-3022

Use a comma to separate coordinate adjectives. Think of these as adjectives that modify the same noun independently: He was a mean, ugly, immoral clown. Note that this is different from noncoordinate adjectives: He wore a bright red Hawaiian shirt.

Page: 199, Location: 3044-3047

Usually, anywhere that and makes sense between the adjectives, you can use a comma in place of and: He was a mean and ugly and immoral clown.

Page: 199, Location: 3047-3049

Use a comma to separate independent clauses joined with a conjunction. This use is optional, but common: We ate the stuffing, but the turkey remained untouched.

Page: 200, Location: 3059-3063

The comma is more likely to be omitted in short, clear sentences in which the independent clauses are joined by and: I like bananas and I like oranges.

Page: 200, Location: 3065-3066