Endurance

pressure of its winds was already crushing the floes

Page: 15, Location: 225-226

The ship reacted to each fresh wave of pressure in a different way. Sometimes she simply quivered briefly as a human being might wince if seized by a single, stabbing pain. Other times she retched in a series of convulsive jerks accompanied by anguished outcries. On these occasions her three masts whipped violently back and forth as the rigging tightened like harpstrings. But most agonizing for the men were the times when she seemed a huge creature suffocating and gasping for breath, her sides heaving against the strangling pressure.

Page: 16, Location: 245-249

More than any other single impression in those final hours, all the men were struck, almost to the point of horror, by the way the ship behaved like a giant beast in its death agonies.

Page: 17, Location: 249-250

Later, to the privacy of his diary, Macklin confided: “I do not think I have ever had such a horrible sickening sensation of fear as I had whilst in the hold of that breaking ship.”

Page: 18, Location: 274-276

His name was Sir Ernest Shackleton, and the twenty-seven men he had watched so ingloriously leaving their stricken ship were the members of his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. The date was October 27, 1915. The name of the ship was Endurance. The position was 69°5' South, 51°30' West—deep in the icy wasteland of the Antarctic’s treacherous Weddell Sea, just about midway between the South Pole and the nearest known outpost of humanity, some 1,200 miles away.

Page: 19, Location: 285-289

It had been very nearly a year since they had last been in contact with civilization. Nobody in the outside world knew they were in trouble, much less where they were. They had no radio transmitter with which to notify any would-be rescuers, and it is doubtful that any rescuers could have reached them even if they had been able to broadcast an SOS. It was 1915, and there were no helicopters, no Weasels, no Sno-Cats, no suitable planes. Thus their plight was naked and terrifying in its simplicity. If they were to get out—they had to get themselves out.

Page: 20, Location: 293-297

There, in 1903, twelve years before, the crew of a Swedish ship had spent the winter after their vessel, the Antarctic, had been crushed by the Weddell Sea ice. The ship which finally rescued that party deposited its stock of stores on Paulet Island for the use of any later castaways. Ironically, it was Shackleton himself who had been commissioned at the time to purchase those stores—and now, a dozen years later, it was he who needed them.

Page: 20, Location: 301-304

The goal of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, as its name implies, was to cross the Antarctic continent overland from west to east.

Page: 21, Location: 312-313

Evidence of the scope of such an undertaking is the fact that after Shackleton’s failure, the crossing of the continent remained untried for fully forty-three years—until 1957–1958. Then, as an independent enterprise conducted during the International Geophysical Year, Dr. Vivian E. Fuchs led the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition on the trek. And even Fuchs, though his party was equipped with heated, tracked vehicles and powerful radios, and guided by reconnaissance planes and dog teams, was strongly urged to give up. It was only after a tortuous journey lasting nearly four months that Fuchs did in fact achieve what Shackleton set out to do in 1915.

Page: 21, Location: 314-318

Then in 1907, Shackleton led the first expedition actually to declare the Pole as its goal. With three companions, Shackleton struggled to within 97 miles of their destination and then had to turn back because of a shortage of food. The return journey was a desperate race with death. But the party finally made it, and Shackleton returned to England a hero of the Empire. He was lionized wherever he went, knighted by his king, and decorated by every major country in the world.

Page: 21, Location: 321-325

Meanwhile, an American expedition under Robert E. Peary had reached the North Pole in 1909. Then Scott, on his second expedition in late 1911 and early 1912, was raced to the South Pole by the Norwegian, Roald Amundsen—and beaten by a little more than a month. It was disappointing to lose out. But that might have been only a bit of miserable luck—had not Scott and his three companions died as they struggled, weak with scurvy, to return to their base.

Page: 22, Location: 330-333

“From the sentimental point of view, it is the last great Polar journey that can be made. It will be a greater journey than the journey to the Pole and back, and I feel it is up to the British nation to accomplish this, for we have been beaten at the conquest of the North Pole and beaten at the first conquest of the South Pole. There now remains the largest and most striking of all journeys—the crossing of the Continent.”

Page: 23, Location: 338-341

In ordinary situations, Shackleton’s tremendous capacity for boldness and daring found almost nothing worthy of its pulling power; he was a Percheron draft horse harnessed to a child’s wagon cart. But in the Antarctic—here was a burden which challenged every atom of his strength.

Page: 25, Location: 380-382

For all his blind spots and inadequacies, Shackleton merited this tribute: “For scientific leadership give me Scott; for swift and efficient travel, Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when there seems no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

Page: 26, Location: 385-388

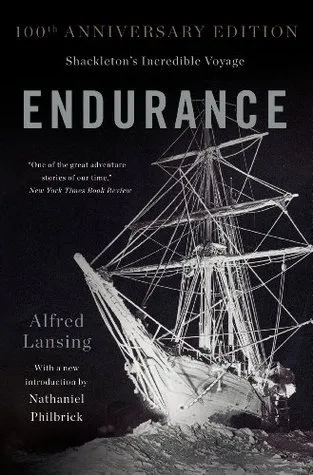

The ship had been named the Polaris. After the sale, Shackleton rechristened her Endurance, in keeping with the motto of his family, Fortitudine vincimus—“By endurance we conquer.”

Page: 27, Location: 402-404

As was the custom, Shackleton also mortgaged the expedition, in a sense, by selling in advance the rights to whatever commercial properties the expedition might produce.

Page: 27, Location: 414-415

In all these arrangements, there was one basic assumption—that Shackleton would survive.

Page: 28, Location: 416-417

By the end of July, 1914, however, everything had been collected, tested, and stowed aboard the Endurance. She sailed from London’s East India Docks on August

Page: 30, Location: 455-457

By the end of July, 1914, however, everything had been collected, tested, and stowed aboard the Endurance. She sailed from London’s East India Docks on August 1.

Page: 30, Location: 455-457

She was designed by Aanderud Larsen so that every joint and every fitting cross-braced something else for the maximum strength. Her construction was meticulously supervised by a master wood shipbuilder, Christian Jacobsen, who insisted on employing men who were not only skilled shipwrights, but had been to sea themselves in whaling and sealing ships.

Page: 32, Location: 490-493

Worsley had thus been appointed captain of the Endurance. That is, he was put in charge of the physical running of the ship under the over-all command of Shackleton, as leader of the entire expedition.

Page: 34, Location: 518-519

The Endurance sailed from Buenos Aires at 10:30 A.M. on October 26 for her last port of call, the desolate island of South Georgia off the southern tip of South America. She proceeded out the ever-widening mouth of the River Platte, and dropped her pilot the next morning at the Recalada Lightship. By sunset the land had dropped from sight.

Page: 36, Location: 539-542

The first land sighted was Saunders Island in the South Sandwich group, and at 6 P.M. on December 7, the Endurance passed between it and the Candlemas Volcano. There, for the first time, she encountered the enemy.

Page: 40, Location: 607-609

That night before he turned in, Greenstreet recorded the day’s events in his diary, concluding the entry with these words: “Here endeth another Christmas Day. I wonder how and under what circumstances our next one will be spent. Temperature 30 degrees.” He would have been shocked could he have guessed. But

Page: 42, Location: 641-645

And Worsley wrote in his log: “We must possess ourselves in patience till a Southerly gale occurs, or the ice opens of its own sweet will.”

Page: 45, Location: 681-682

For three hours the ship leaned against the ice with all her might—and never moved a foot. The Endurance was beset. As Orde-Lees, the storekeeper, put it, “frozen, like an almond in the middle of a chocolate bar.”

Page: 45, Location: 685-687

Worsley’s diary tells the story of day after day of waiting for the gale that never came: “Light SW breeze”. . . . “Mod. East’ly breeze”. . . . “Gentle SW breeze”. . . . “Calm and light airs”. . . . “Light West’ly breezes.”

Page: 46, Location: 696-697

Then, on February 14, an excellent lead of water opened a quarter of a mile ahead of the ship. Steam was hurriedly raised and all hands were ordered onto the ice with saws, chisels, picks, and any other tools that could be used to cut a lane through the floes. The Endurance lay in a pool of young ice only about a foot or two thick. This was systematically sawed and rafted away to give the ship room to batter at the floes ahead. The crew started work at 8:40 A.M., and worked throughout the day. By midnight they had carved out a channel about 150 yards long.

Page: 48, Location: 724-729

Greenstreet, always plain-spoken and never one to dodge the issue, summed up the general feeling in his diary that night. In a tired hand, he wrote: “Anyway, if we do get jambed here for the winter we shall have the satisfaction of knowing that we did our darnest to try & get out.”

Page: 49, Location: 743-745

Their time was running out. They noticed the approaching end of the Antarctic summer on February 17 when the sun, which had shone twenty-four hours a day for two months, dipped beneath the horizon for the first time at midnight.

Page: 49, Location: 746-747

He was careful, however, not to betray his disappointment to the men, and he cheerfully supervised the routine of readying the ship for the long winter’s night ahead.

Page: 50, Location: 766-767

The conversion of the Endurance from a ship into a kind of floating shore station brought with it a marked slowdown in the tempo of life. There simply wasn’t much for the men to do. The winter schedule required of them only about three hours’ work a day, and the rest of the time they were free to do what they wanted.

Page: 51, Location: 770-773

On May 2, their position showed a total northwest drift since the end of February of 130 miles. The Endurance was one microcosmic speck, 144 feet long and 25 feet wide, embedded in nearly one million square miles of ice that was slowly being rotated by the irresistible clockwise sweep of the winds and currents of the Weddell Sea.

Page: 54, Location: 817-819

In all the world there is no desolation more complete than the polar night. It is a return to the Ice Age—no warmth, no life, no movement. Only those who have experienced it can fully appreciate what it means to be without the sun day after day and week after week. Few men unaccustomed to it can fight off its effects altogether, and it has driven some men mad.

Page: 55, Location: 832-834

Each Saturday night before the men turned in a ration of grog was issued to all hands, followed by the toast, “To our sweethearts and wives.” Invariably a chorus of voices added, “May they never meet.”

Page: 60, Location: 910-912

The men’s thoughts began to turn to spring, the return of the sun and warmth when the Endurance would break out of her icy prison and they could make a new assault on Vahsel Bay.

Page: 63, Location: 961-963

been two pieces of cork. When he got back to the ship, Greenstreet wrote in his diary:

Page: 66, Location: 1003-1004

When he got back to the ship, Greenstreet wrote in his diary: “Lucky for us if we don’t get any pressure like that against the ship for I doubt whether any ship could stand a pressure that will force blocks like that up.”

Page: 66, Location: 1004-1005

Worsley, after recording the day’s events, concluded the entry in his diary that evening: “If anything held the ship from rising to such pressure she would crush up like an empty eggshell. The behavior of the dogs was splendid. . . . They seemed to regard it as an entertainment we had got up for their benefit.”

Page: 68, Location: 1028-1030

“Many of the tabular bergs appear like huge warehouses and grain elevators, but more look like the creations of some brilliant architect when suffering from delirium, induced by gazing too long on this damned infernal stationary pack that seems . . . doomed to drift to and fro till the Crack of Doom splits and shivers it N., S., E. & W. into a thousand million fragments—and the smaller the better. No animal life observed—no land—no nothing!!!”

Page: 72, Location: 1095-1098

On October 10, the thermometer climbed to 9.8 degrees above zero. The floe which had been jammed under the ship’s starboard side since July broke free on October 14, and the Endurance lay in a small pool of open water—truly afloat for the first time since she was beset nine months before.

Page: 74, Location: 1125-1128

rudder. They finished about 10 P.M. A ration of grog

Page: 76, Location: 1155-1156

The sailors stopped what they were doing, and old Tom McLeod turned to Macklin. “Do you hear that?” he asked. “We’ll none of us get back to our homes again.” Macklin noticed Shackleton bite his lip.

Page: 79, Location: 1211-1213

The plan, as they all knew, was to march toward Paulet Island, 346 miles to the northwest, where the stores left in 1902 should still be. The distance was farther than from New York City to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and they would be dragging two of their three boats with them, since it was assumed that they would eventually run into open water.

Page: 82, Location: 1258-1260

He also tore out the page from the Book of Job with this verse on it: “Out of whose womb came the ice? And the hoary frost of Heaven, who hath gendered it? The waters are hid as with a stone. And the face of the deep is frozen.”

Page: 84, Location: 1282-1286

The journey would begin the next day. On the eve of setting out, Shackleton wrote: “I pray God I can manage to get the whole party safe to civilization.”

Page: 85, Location: 1295-1296

October 30 was gray and overcast with a bit of occasional wet snow. The temperature was an uncomfortably warm 15 degrees, which made the surface of the ice soft—far from ideal for sledging.

Page: 85, Location: 1296-1297

Worsley, however, was far from distressed. He wrote in his diary that same night: “The rapidity with which one can completely change one’s ideas . . . and accommodate ourselves to a state of barbarism is wonderful.” Shackleton was pleased by the general cheeriness of the men. “Many look on this as a spree,” he recorded. “It is better so.” He also observed: “This floe really strong. Will sleep tonight.”

Page: 87, Location: 1331-1335

They were castaways in one of the most savage regions of the world, drifting they knew not where, without a hope of rescue, subsisting only so long as Providence sent them food to eat. And yet they had adjusted with surprisingly little trouble to their new life, and most of them were quite sincerely happy. The adaptability of the human creature is such that they actually had to remind themselves on occasion of their desperate circumstances

Page: 90, Location: 1366-1369

Though he was virtually fearless in the physical sense, he suffered an almost pathological dread of losing control of the situation. In part, this attitude grew out of a consuming sense of responsibility. He felt he had gotten them into their situation, and it was his responsibility to get them out. As a consequence, he was intensely watchful for potential troublemakers who might nibble away at the unity of the group.

Page: 94, Location: 1433-1436

With Shackleton, however, he was obsequious—an attitude which Shackleton detested. Shackleton, like almost everybody else, disliked Orde-Lees intensely and even told him so once. Characteristically, Orde-Lees dutifully recorded the incident in his diary, writing it in the third person as if he had been an onlooker during the conversation.

Page: 99, Location: 1516-1518

The subject of sex was rarely brought up—not because of any post-Victorian prudishness, but simply because the topic was almost completely alien to the conditions of cold, wet, and hunger which occupied everyone’s thoughts almost continually. Whenever women were discussed, it was in a nostalgic, sentimental way—of a longing to see a wife, a mother, or a sweetheart at home.

Page: 104, Location: 1585-1588

Shackleton that night noted simply in his diary that the Endurance was gone, and added: “I cannot write about it.” And so they were alone. Now, in every direction, there was nothing to be seen but the endless ice. Their position was 68°38½′ South, 52°28′ West—a place where no man had ever been before, nor could they conceive that any man would ever want to be again.

Page: 106, Location: 1620-1623

Shackleton’s aversion to tempting fate was well known. This attitude had earned for him the nickname “Old Cautious” or “Cautious Jack.” But nobody ever called him that to his face. He was addressed simply as “Boss”—by officers, scientists, and seamen alike. It was really more a title than a nickname. It had a pleasant ring of familiarity about it, but at the same time “Boss” had the connotation of absolute authority. It was therefore particularly apt, and exactly fitted Shackleton’s outlook and behavior.

Page: 109, Location: 1657-1661

In essence the note said that the Endurance had been crushed and abandoned at 69°5´ South, 51°35´ West, and that the members of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition were then at 67°9´ South, 52°25´ West, and proceeding to the west across the ice in the hope of reaching land. The message concluded: “All well.” It was dated December 23, 1915, and signed, “Ernest Shackleton.” Worsley placed the bottle with its message in the stern of the Stancomb Wills back at Ocean Camp.

Page: 116, Location: 1766-1771

None of them, however, could possibly have felt their defeat so intensely as Shackleton, to whom the thought of quitting was abhorrent. He wrote in his diary that night, with characteristically peculiar punctuation: “Turned in but could not sleep. Thought the whole matter over & decided to retreat to more secure ice: it is the only safe thing to do. . . . Am anxious: For so big a party & 2 boats in bad conditions we could do nothing: I do not like retreating but prudence demands this course: Everyone working well except the carpenter: I shall never forget him in this time of strain & stress.”

Page: 121, Location: 1847-1851

Macklin noted: “The last day of 1915 . . . tomorrow 1916 begins: I wonder what it will bring forth for us. This time last year we prophesied that just now we would be well across the Continent.” Finally, Shackleton wrote: “The last day of the old year: May the new one bring us good fortune, a safe deliverance from this anxious time & all good things to those we love so far away.” part III

Page: 122, Location: 1866-1878

This indomitable self-confidence of Shackleton’s took the form of optimism. And it worked in two ways: it set men’s souls on fire; as Macklin said, just to be in his presence was an experience. It was what made Shackleton so great a leader.

Page: 127, Location: 1942-1943

But at the same time, the basic egotism that gave rise to his enormous self-reliance occasionally blinded him to realities. He tacitly expected those around him to reflect his own extreme optimism, and he could be almost petulant if they failed to do so. Such an attitude, he felt, cast doubt on him and his ability to lead them to safety.

Page: 127, Location: 1944-1946

“I am rather tired,” he wrote one day. “I suppose it is the strain.” Then later, “I long for some rest, free from thought.”

Page: 128, Location: 1950-1951

Under the best circumstances it would have been upsetting news. Under their present circumstances it was amplified in the minds of some men almost to a catastrophe. In their bitterness, a few, like Greenstreet, were inclined to fix the blame on Shackleton—with some justification: “. . . the present shortage of food,” Greenstreet wrote, “is due simply and solely from the Boss refusing to get seals when they were to be had and even refusing to let Orde-Lees to go out to look for them. . . . His sublime optimism all the way thro being to my mind absolute foolishness. Everything right away thro was going to turn out all right and no notice was taken of things possibly turning out otherwise and here we are.”

Page: 129, Location: 1975-1980

Lying in his sleeping bag that night, Macklin wearily recorded the events of the journey in his diary. In a tired hand he concluded the entry: “My dogs will be shot tomorrow.”

Page: 131, Location: 2008-2009

That night Shackleton wrote, almost timorously, “This may be the turn in our fortune.”

Page: 133, Location: 2027-2028

“Wonderful, amazing splendid,” Shackleton wrote. “Lat. 65°43' South—73 miles North drift. The most cheerful good fortune for a year for us: We cannot be much more than 170 miles from Paulet. Everyone greeted the news with cheers. The wind still continues. We may get another 10 miles out of it. Thank God. Drifting still all wet in the tents but no matter. Had bannock to celebrate North of the circle.” The Antarctic Circle now lay nearly a full degree of latitude behind them.

Page: 134, Location: 2044-2047

On the twenty-sixth, after a day of unrelieved monotony, he took his diary and wrote across the space provided for that day: “Waiting Waiting Waiting.”

Page: 135, Location: 2061-2063

“We also suffer from ‘Amenomania’” [literally—wind-madness], he wrote later. “This disease may be exhibited in two forms: Either one is morbidly anxious about the wind direction and gibbers continually about it, or else a sort of lunacy is produced by listening to the other Amenomaniacs. The second form is more trying to hear. I have had both.”

Page: 139, Location: 2121-2124

Macklin noted: “We have just been a third of a year on the floe, drifting as Nature has willed. I wonder when we shall see home again.”

Page: 141, Location: 2161-2162

Shackleton alone seemed to sense in the swell a new and far more grave threat than almost any they had faced. He wrote that night: “Trust will not increase until leads form.”

Page: 145, Location: 2215-2217

In fifteen minutes, Patience Camp was lost in the confusion of ice astern. But Patience Camp no longer mattered. That soot-blackened floe which had been their prison for nearly four months—whose every feature they knew so well, as convicts know each crevice of their cells; which they had come to despise, but whose preservation they had prayed for so often—belonged now to the past. They were in the boats . . . actually in the boats, and that was all that mattered. They thought neither of Patience Camp nor of an hour hence. There was only the present, and that meant row . . . get away . . . escape.

Page: 173, Location: 2653-2657

It was named in honor of Edward Bransfield, who, in 1820, took a small brig named the Williams into the waters which now bear his name. According to the British, Bransfield was thus the first man ever to set eyes on the Antarctic Continent.

Page: 175, Location: 2676-2677

Worsley wrote; “By my reckoning we make today [northwest] 10 miles, and the current should run us well to

Page: 183, Location: 2806-2806

Worsley wrote; “By my reckoning we make today [northwest] 10 miles, and the current should run us well to the West before this strong Easterly breeze.”

Page: 183, Location: 2806-2807

It was as if they had suddenly emerged into infinity. They had an ocean to themselves, a desolate, hostile vastness. Shackleton thought of the lines of Coleridge: “Alone, alone, all, all alone, Alone on a wide wide sea.” They made a pitiable sight—three little boats, packed with the odd remnants of what had once been a proud expedition, bearing twenty-eight suffering men in one final, almost ludicrous bid for survival. But this time there was to be no turning back, and they all knew it. The

Page: 196, Location: 2998-3003

It was the merest handhold, 100 feet wide and 50 feet deep. A meager grip on a savage coast, exposed to the full fury of the sub-Antarctic Ocean. But no matter—they were on land. For the first time in 497 days they were on land. Solid, unsinkable, immovable, blessed land.

Page: 214, Location: 3281-3283

It was the same for all of them. “How delicious,” wrote Hurley, “to wake in one’s sleep and listen to the chanting of the penguins mingling with the music of the sea. To fall asleep and awaken again and feel this is real. We have reached the land!!”

Page: 217, Location: 3324-3326

Most of the men were awakened once during that glorious night to stand an hour’s watch, and even this was almost pleasure. The night was calm, and the sky was clear. The moon shone on the little pebbled beach, washed by the waves, a scene of utter tranquility. Furthermore, wrote Worsley, the watchmen, during their 1-hour tour of duty, “feed themselves, keep the blubber fire going, feed themselves, dry their clothes, feed themselves, and then feed themselves again before turning in.”

Page: 217, Location: 3327-3330

It was a joy, for example, to watch the birds simply as birds and not for the significance they might have—whether they were a sign of good or evil, an opening of the pack or a gathering storm

Page: 219, Location: 3347-3348

It was April 20, a day notable for only one reason: Shackleton finally made official what everyone had expected for a long time. He would take a party of five men and set sail in the Caird for South Georgia to bring relief. They would leave as soon as the Caird could be made ready and provisioned for the trip.

Page: 225, Location: 3445-3448

Hurley buttonholed Shackleton, who signed the following letter in Hurley’s diary: 21st April, 1916 To whom this may concern viz. my executors assigns etc. Under is my signature to the following instructions. In the event of my not surviving the boat journey to South Georgia I here instruct Frank Hurley to take complete charge & responsibility for exploitation of all films & photographic reproductions of all films & negatives taken on this Expedition the aforesaid films & negatives to become the property of Frank Hurley after due exploitation, in which, the moneys to be paid to my executors will be according to the contract made at the start of the expedition. The exploitation expires after a lapse of eighteen months from date of first public display. I bequeath the big binoculars to Frank Hurley. E. H. SHACKLETON

Page: 229, Location: 3503-3511

It was just twelve-thirty. The three little sails on the Caird were up when the men ashore saw McCarthy in the bow signaling to cast off the bow line. Wild let go of it, and McCarthy hauled it in. The party on shore gave three cheers, and across the surging breakers they heard three small shouts in reply. The Caird caught the wind, and Worsley at the helm swung her bow toward the north.

Page: 235, Location: 3601-3604

Hurley wrote: “Life here without a hut and equipment is almost beyond endurance.” But little by little, as the wind revealed their vulnerable spots, they sealed them up, and each day the shelter became just a little more livable.

Page: 239, Location: 3655-3657

In short, we want to be overfed, grossly overfed, yes, very grossly overfed on nothing but porridge and sugar, black currant and apple pudding and cream, cake, milk, eggs, jam, honey and bread and butter till we burst, and we’ll shoot the man who offers us meat. We don’t want to see or hear of any more meat as long as we live.”

Page: 242, Location: 3705-3707

Macklin wrote on May 22: “There is a big change in the scenery about here—everything is now covered with snow, and there is a considerable ice foot to both sides of the spit. For the last few days ice has been coming in, and dense pack extends in all directions as far as the eye can reach, making the chances of a near rescue seem very remote. No ship but a properly constructed ice-ship would be safe in this pack; an iron steamer would be smashed up very soon. Besides this there is very little daylight now. . .

Page: 244, Location: 3735-3739

On May 25, one month and one day after the Caird had sailed, Hurley wrote: “Weather drifting snow and wind from east. Our wintry environment embodies the most inhospitable and desolate prospect imaginable. All are resigned now and fully anticipate wintering.”

Page: 244, Location: 3740-3742

After a time, however, Wild succumbed to mounting pressure and a 2-gallon gasoline can was made into a urinal for use at night. The rule was that the man who raised its level to within 2 inches of the top had to carry the can outside and empty it. If a man felt the need and the weather outside was bad, he would lie awake waiting for somebody else to go so that he might judge from the sound the level of the can’s contents.

Page: 247, Location: 3778-3781

More than once, a man would fill the can as silently as possible, then steal back into his sleeping bag. The next man to get up would find to his fury that the can was full—and had to be emptied before it could be used.

Page: 247, Location: 3783-3784

Greenstreet recorded one evening: “Everyone spent the day rotting in their bags with blubber and tobacco smoke—so passes another goddam rotten day.”

Page: 248, Location: 3790-3791

“Horrible taste,” wrote Macklin. “It served only to turn most of us teetotalers for life, except for a few who pretended to like it. . . . Several felt ill after.”

Page: 252, Location: 3859-3860

Hurley recorded on July 16: “Go for my Sunday promenade. The well beaten 100 yards on the spit. This one would not tire of provided we knew Sir E. and the crew of the ‘Caird’ were safe and when relief could be definitely expected. We speculate about the middle of August. . . .” This, then, became the target date—the time, as it were, when they might begin to worry officially. Wild purposely made it as remote as he reasonably could to keep their hopes alive as long as possible.

Page: 253, Location: 3867-3870

“It is hard to realize one’s position here,” Macklin wrote, “living in a smoky, dirty, ramshackle little hut with only just sufficient room to cram us all in: drinking out of a common pot . . . and laying in close proximity to a man with a large discharging abscess—a horrible existence, but yet we are pretty happy. . . .”

Page: 256, Location: 3920-3922

August 1 was the anniversary of the day, two years before, when the Endurance had sailed from London, and one year before, when she had sustained her first serious pressure.

Page: 257, Location: 3940-3942

The memories of everything up to now, he wrote, “flit through our minds as a chaotic, confused nightmare. The past twelve months appear to have passed speedily enough and though we have been dwelling here in a life of security for nearly 4 months, this latter period seems longer than the preceding balance of the year. This doubtless is occasioned by our counting the days and the daily expectations of deferred relief, as well as our having no . . . work to perform. . . . The watching day by day and the anxiety for the safety of our comrades of the Caird lay a holding hand on the already retarded passage of time.”

Page: 258, Location: 3942-3947

Unlike the land, where courage and the simple will to endure can often see a man through, the struggle against the sea is an act of physical combat, and there is no escape. It is a battle against a tireless enemy in which man never actually wins; the most that he can hope for is not to be defeated.

Page: 264, Location: 4047-4049

Charles Darwin, on first seeing these waves breaking on Tierra del Fuego in 1833, wrote in his diary: “The sight . . . is enough to make a landsman dream for a week about death, peril and shipwreck.”

Page: 270, Location: 4133-4135

The sight that the Caird presented was one of the most incongruous imaginable. Here was a patched and battered 22-foot boat, daring to sail alone across the world’s most tempestuous sea, her rigging festooned with a threadbare collection of clothing and half-rotten sleeping bags. Her crew consisted of six men whose faces were black with caked soot and half-hidden by matted beards, whose bodies were dead white from constant soaking in salt water.

Page: 282, Location: 4321-4325

Worsley took out his log and wrote: “Moderate sea, Southerly swell Blue sky; passing clouds. Fine. Clear weather. Able to reduce some parts of our clothing from wet to damp. To Leith Harb. 347. m [miles]”

Page: 283, Location: 4329-4332

And so that peculiar brand of anxiety, born of an impossible goal that somehow comes within reach, began to infect them. Nothing overt, really, just a sort of added awareness, a little more caution and more care to insure that nothing preventable should go wrong now.

Page: 284, Location: 4342-4344

For thirteen days they had absorbed everything that the Drake Passage could throw at them—and now, by God, they deserved to make it.

Page: 287, Location: 4389-4390

The strain on Shackleton was so great that he lost his temper over a trivial incident. A small, bob-tailed bird appeared over the boat and flew annoyingly about, like a mosquito intent on landing. Shackleton stood it for several minutes, then he leaped to his feet, swearing and batting furiously at the bird with his arms. But he realized at once the poor example he had set and dropped back down again with a chagrined expression on his face.

Page: 287, Location: 4398-4401

through the reefs. Worsley took out his navigation book again and wrote this: “. . . Heavy westerly swell. Very bad lumpy sea. Stood off for night; wind increasing. .

Page: 295, Location: 4511-4513

Worsley thought to himself of the pity of it all. He remembered the diary he had kept ever since the Endurance had sailed from South Georgia almost seventeen months before. That same diary, wrapped in rags and utterly soaked, was now stowed in the forepeak of the Caird. When she went, it would go, too. Worsley thought not so much of dying, because that was now so plainly inevitable, but of the fact that no one would ever know how terribly close they had come.

Page: 300, Location: 4599-4603

It was five o’clock on the tenth of May, 1916, and they were standing at last on the island from which they had sailed 522 days before. They heard a trickling sound. Only a few yards away a little stream of fresh water was running down from the glaciers high above. A moment later all six were on their knees, drinking.

Page: 303, Location: 4644-4647

They ate them for supper, and Worsley wrote of the older bird: “Good eating but rather tough.” McNeish noted simply: “It was a treat.”

Page: 308, Location: 4713-4714

It was an utterly carefree journey as the Caird drove smartly across the sparkling water. After a while they even began to sing. It occurred to Shackleton that they could easily have been mistaken for a picnic party out for a lark—except perhaps for their woebegone appearance.

Page: 309, Location: 4732-4734

The Caird was hauled above the reach of the water, and then they turned her over. McCarthy shored her up with a foundation of stones and when she was ready, they arranged their sleeping bags inside. It was decided to name the place “Peggotty Camp,” after the poor but honest family in Dickens’ David Copperfield.

Page: 309, Location: 4736-4739

The only superfluous item Shackleton permitted was Worsley’s diary.

Page: 311, Location: 4755-4756

Worsley and Crean were stunned—especially for such an insane solution to be coming from Shackleton. But he wasn’t joking . . . he wasn’t even smiling. He meant it—and they knew it. But what if they hit a rock, Crean wanted to know.

Page: 317, Location: 4851-4853

Each of them coiled up his share to form a mat. Worsley locked his legs around Shackleton’s waist and put his arms around Shackleton’s neck. Crean did the same with Worsley. They looked like three tobogganers without a toboggan.

Page: 317, Location: 4859-4860

They looked up against the darkening sky and saw the fog curling over the edge of the ridges, perhaps 2,000 feet above them—and they felt that special kind of pride of a person who in a foolish moment accepts an impossible dare—then pulls it off to perfection.

Page: 318, Location: 4868-4870

Suddenly he jerked his head upright. All the years of Antarctic experience told him that this was the danger sign—the fatal sleep that trails off into freezing death. He fought to stay awake for five long minutes, then he woke the others, telling them that they had slept for half an hour.

Page: 320, Location: 4894-4896

A peculiar thing to stir a man—the sound of a factory whistle heard on a mountainside. But for them it was the first sound from the outside world that they had heard since December, 1914—seventeen unbelievable months before. In that instant, they felt an overwhelming sense of pride and accomplishment. Though they had failed dismally even to come close to the expedition’s original objective, they knew now that somehow they had done much, much more than ever they set out to do.

Page: 321, Location: 4913-4916

For a very long moment they stared without speaking. There didn’t really seem to be very much to say, or at least anything that needed to be said. “Let’s go down,” Shackleton said quietly. Having got so close, his old familiar caution returned, and he was determined that nothing was to go wrong now.

Page: 322, Location: 4930-4933

Worsley reached under his sweater and carefully took out four rusty safety pins that he had hoarded for almost two years. With them he did his best to pin up the major rents in his trousers.

Page: 323, Location: 4950-4951

“Who the hell are you?” he said at last. The man in the center stepped forward. “My name is Shackleton,” he replied in a quiet voice. Again there was silence. Some said that Sørlle turned away and wept. epilogue The crossing of South Georgia has been accomplished only by one other party.

Page: 325, Location: 4982-4991

“Who the hell are you?” he said at last. The man in the center stepped forward. “My name is Shackleton,” he replied in a quiet voice. Again there was silence. Some said that Sørlle turned away and wept.

Page: 325, Location: 4982-4984

“We to-day are travelling easily and unhurriedly. We are fit men, with our sledges and tents and ample food and time. We break new ground but with the leisure and opportunity to probe ahead. We pick and choose our hazards, accepting only the calculated risk. No lives depend upon our success—except our own. We take the high road. “They—Shackleton, Worsley and Crean . . . took the low road. “I do not know how they did it, except that they had to—three men of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration with 50 feet of rope between them—and a carpenter’s adze.”

Page: 326, Location: 4996-5000

Their spokesman, speaking in Norse with Sørlle translating, said that they had sailed the Antarctic seas for forty years, and that they wanted to shake the hands of the men who could bring an open 22-foot boat from Elephant Island through the Drake Passage to South Georgia.

Page: 327, Location: 5012-5014

Of the honors that followed—and there were many—possibly none ever exceeded that night of May 22, 1916, when, in a dingy warehouse shack on South Georgia, with the smell of rotting whale carcasses in the air, the whalermen of the southern ocean stepped forward one by one and silently shook hands with Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean.

Page: 328, Location: 5018-5020

Five days later, on August 30, Worsley logged: “5.25 am Full speed . . . 11.10 [A.M.] . . . base of land faintly visible. Threadg: our way between lumps ice, reefs, & grounded bergs. 1.10 PM Sight the Camp to sw. . . .”

Page: 329, Location: 5039-5042

“Hadn’t we better send up some smoke signals?” he asked. For a moment there was silence, and then, as one man, they grasped what Marston was saying. “Before there was time for a reply,” Orde-Lees recorded, “there was a rush of members tumbling over one another, all mixed up with mugs of seal hoosh, making a simultaneous dive for the door-hole which was immediately torn to shreds so that those members who could not pass through it, on account of the crush, made their exits through the ‘wall,’ or what remained of it.”

Page: 330, Location: 5057-5062

Within a few minutes the boat was near enough for Shackleton to be heard. “Are you all right?” he shouted. “All well,” they replied.

Page: 332, Location: 5077-5078

Wild urged Shackleton to come ashore, if only briefly, to see how they had fixed the hut in which they had waited four long months. But Shackleton, though he was smiling and obviously relieved, was still quite noticeably anxious and wanted only to be away. He declined Wild’s offer and urged the men to get on board as quickly as possible.

Page: 332, Location: 5080-5083

Throughout it all Worsley had watched anxiously from the bridge of the ship. Finally he logged: “2.10 All Well! At last! 2.15 Full speed ahead.”

Page: 332, Location: 5086-5087

Macklin wrote: “I stayed on deck to watch Elephant Island recede in the distance . . . I could still see my Burberry [jacket] flapping in the breeze on the hillside—no doubt it will flap there to the wonderment of gulls and penguins till one of our familiar [gales] blows it all to ribbons.”

Page: 332, Location: 5088-5090